Dyslexia is a difficulty, more prevalent in men, with reading and spelling. Mslexia is a difficulty, more prevalent in women, with getting published. Founder Debbie Taylor isolates the causes of mslexia – and suggests a few cures

Imagine an alien boffin arriving on earth for the first time, say just outside Ipswich. Its five-year mission: an intergalactic survey of gender and writing. It begins – as on every planet it visits – with a look at the young of the dominant species. In nurseries and classrooms throughout the land, it notices immature females are significantly more advanced than males in every aspect of linguistic development.

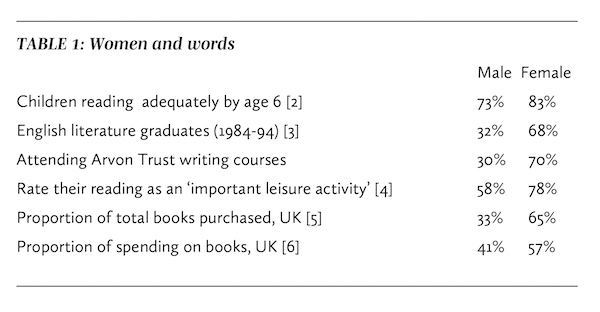

Young females speak, read and write sooner than males, are generally more diligent and talented in linguistic subjects, and gain better results in examinations. Young males, on the other hand, are over three times more likely to suffer from a kind of reading and writing difficulty known as ‘dyslexia’[1]. Turning to the adults, it finds that wherever literature or writing is being studied there are more females than males in the classrooms. The females buy and borrow more books, and spend more time reading – especially fiction and poetry (the males being, for some reason, more interested in non-fiction).

Transporting to other land masses, the alien discovers this is a planet-wide phenomenon. It appears female brains are organised to be particularly adept at verbal skills (perhaps, it muses, because females on this planet seem responsible for instructing the offspring). Whatever the reason, the females display a consistent pattern of literary superiority (Table I).

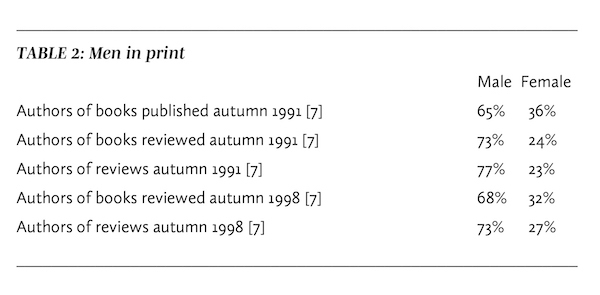

Just then the alien notices a newspaper listing the 100 best books of the century. Confident that female authors will predominate, it scans an eye down the list with a yawn. Then sits up with a start: the authors are nearly all males! (Table 2)

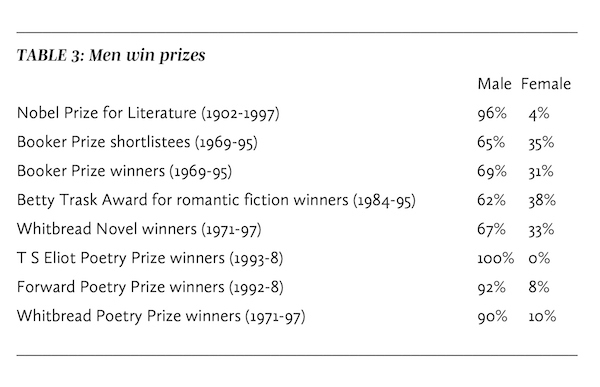

Thinking this must be a mistake, it fast-backwards through several years of newsprint and discovers that books by males are mentioned twice as often as books by females (Table 3), and that they are twice as likely to be shortlisted for or to win literary prizes.

What on earth is going on, it wonders. Sighing, it unfurls its pyjamas and prepares for a long stay.

What woman writers need

This discrepancy between women’s literary potential and their actual achievement is the starting point for this magazine. And we have coined a new word – mslexia – to describe it.

Mslexia’s surface meaning is women’s writing (ms= woman, lexia = words). But its association with dyslexia is intentional. Dyslexia is a difficulty, more prevalent in males, with reading and spelling. Mslexia is a difficulty, more prevalent in females, with getting published. More specifically, mslexia is the complex set of conditions and expectations which prevents women, who as girls so outshine boys in verbal skills, from becoming successful authors.

The good news is that, like dyslexia, mslexia can be overcome. That’s what this magazine is about: exploring the causes of mslexia – and suggesting some cures.

So what is it that men have, that women need, to become noted authors? Virginia Woolf’s famous prescription was ‘money and a room of one’s own’. Mslexia’s prescription, gleaned from historical, psychological and social research – and a few specially-commissioned surveys of our own – is slightly different. The three things that male writers have, that woman writers need, are: time, confidence and a fair reading.

'The three things that male writers have, that woman writers need, are: time, confidence and a fair reading'

Time

Survey after survey has found that women spend more time on housework and childcare than men: exactly twice as much according to the 1997 study of housework in the UK from the Office for National Statistics [8]. Yes, even when they go out to work, even with washing machines and child-minders, even (dare we say it?) in the era of the New Man.

So it was for Mrs Gaskell at the birth of the novel, complaining that ‘everybody comes in to me perpetually’ while ‘Mr Gaskell just trots off to his study’ [9]. And for Sylvia Plath a century later, forced to get up at ‘four in the morning, that still blue almost eternal hour before the baby’s cry’ [10]. So, as Barbara Trapido attests in our lead interview, is it today for the majority of woman writers.

'male writers usually have wives, lovers, mothers, to run their homes and patrol the quiet solitude creativity demands'

Candia McWilliam spoke for many when she claimed that ‘one child equals two unwritten books’. And a recent survey of woman journalists uncovered hundreds of careers downsized or abandoned as promising writers gave up trying to combine motherhood with the long hours they were expected to work [11]. Journalist Jill Tweedie wrote of the ‘fury [that] continually rose in me … the toing and fro-ing [that] exhausted me’ [12].

It’s no coincidence that so many prominent woman authors – today and throughout the history – have been either childless, or lesbian, or both. The so-called Five Great woman novelists – the Brontës, Jane Austen, George Eliot and Virginia Woolf – were all without children.

The enervatingly obvious point is that male writers usually have wives, lovers, mothers, to run their homes and patrol the quiet solitude creativity demands.

As Katia Mann (wife of Thomas Mann) said: ‘My portion was to see to it that he had the best circumstances for his work’ [13]. ‘After we were married he wrote more,’ boasted a proud Mrs William Carlos Williams. ‘I saw to it that he had time.’[14] What woman writer can say that of her husband?

‘They said of Tolstoy that it was lucky his wife could decipher his scribbles. Well, I’ve compared those scribbles with what his wife came up with – she was a brilliant writer’

The result, according to Tillie Olsen, is ‘sporadic effort and unfinished work … years and years in getting one book done … numbers of women who not until their forties, fifties, sixties, publish for the first time’ [15]. Olsen’s passionate polemic Silences was one of the first to investigate women’s relative absence from the literary canon. Her baton was passed to Dale Spender, a founder of Pandora Press and author of the ground-breaking Man Made Language [16] and more recently to Kate Mosse, chief architect of the Orange Prize for women’s fiction.

Spender suggests some male authors get more than domestic services from their wives. ‘They said of Tolstoy that it was lucky his wife could decipher his scribbles,’ she told us in a recent interview. ‘Well, I’ve looked at those scribbles, and I’ve compared them with what his wife came up with – and I reckon she was a brilliant writer.’ So why wasn’t she writing books of her own?

Confidence

Spender believes lack of confidence may be even more of a handicap than lack of time for a woman author. Even if they prefer to read other women’s writing themselves, everything else women read – the reviews, the interviews, the literary shortlists – tells them that men’s writing is the work of true quality. ‘With so few acclaimed woman writers, there’s this feeling of: “What if it’s got to start with me? I’m not clever enough. I’ll never be good enough.”‘

But on researching British literary history Spender discovered what amounts to a confidence trick against women writers: that there were no less than 100 good women writers before Jane Austen. But only 25 men. Five of those men have been acclaimed as the Fathers of the Novel. But all of the 100 women – many of whom enjoyed ‘dazzling prestige’ during their careers – have vanished almost without trace [17].

'There were no less than 100 good women writers before Jane Austen. But only 25 men'

She’s not suggesting malice aforethought on the part of the male publishers: more a subconscious closing of the ranks (which she believes still takes place in many publishing houses today). So that when choices had to be made about which books to reprint, the women’s were quietly dropped off the lists.

What dropped away with them is a sense of literary continuity. As poet Adrienne Rich put it in Lies, Secrets and Silence: ‘women’s work and thinking has been made to seem sporadic, erratic, orphaned of any tradition of its own’[18].

But lack of literary tradition is not the only thing undermining women’s confidence as authors. Evidence spanning more than two decades reveals a deeper kind of rot that sets in far earlier, while they are children. Two years ago psychologists Frank Pajares and Margaret Johnson discovered that schoolgirls consistently underestimate the quality of their own writing; boys had a much more realistic assessment [19]. Earlier research, asking children to guess their ranking in class, found that even when they were doing better than the boys, girls expected to do worse [20].

'if a boy does well, he’s described as ‘clever’ or ‘gifted’; if a girl does well, her achievement is often attributed to ‘mere’ hard work and maturity'

Spender confirmed these results with her own experiments in three different countries, and tried to disentangle the roots of the girls’ lack of confidence. It stemmed, she concluded, from two different sets of standards being applied to girls’ and boys’ achievements.

When a boy does badly, she discovered (at writing, or anything else for that matter), it is frequently attributed to his lack of application or maturity, with comments like ‘he doesn’t concentrate’, or ‘he needs to settle down’. When a girl does badly, she’s more likely to be thought less intelligent. Conversely, if a boy does well, he’s described as ‘clever’ or ‘gifted’. If a girl does well, her achievement is often attributed to ‘mere’ hard work and maturity [21].

This double standard, she concludes, ‘promotes self-confidence and high self esteem among the boys’ – and undermines it in the girls. As Michele Stanforth discovered in her research: boys tend to attribute a poor performance to bad luck or laziness – so success simply confirms their blithe belief in their ability. But girls attribute failure to a lack of ability, which causes them to withdraw rather than work harder [22].

'girls attribute failure to a lack of ability, which causes them to withdraw rather than work harder'

It makes sense. If failure makes you feel inadequate – as opposed to unlucky – you’re going to feel much more wary of exposing yourself to it.

That this can have a profound effect on creativity is suggested by a series of quite dramatic experiments conducted recently by psychologist John Baer. He found that when girls thought their poems and stories were going to be evaluated by experts, it ‘markedly’ undermined their creativity compared with when they were writing without the prospect of criticism. For boys, knowing their work would be judged by experts made no difference to their performance [23].

More recent research found a similar effect in adults: the quality of women’s writing deteriorated when they thought their work would be seen by an audience of readers; whereas men’s writing improved significantly [24].

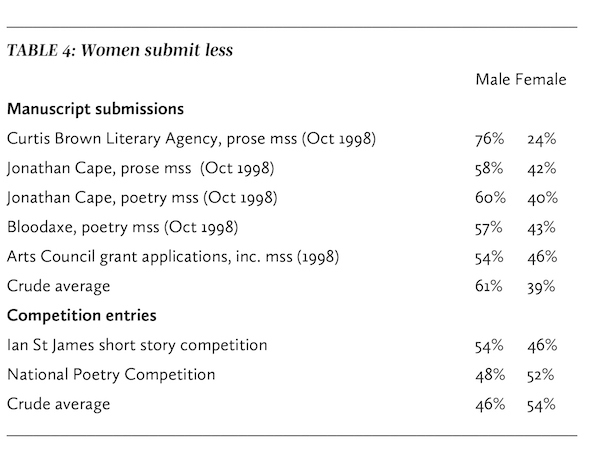

These findings make sense of the results of Mslexia’s own specially-commissioned surveys of fiction and poetry publishers and authors’ agents, which revealed that women are over 50 per cent less likely than men to submit their work for publication (Table 4).

Commenting on an equivalent phenomenon in the world of journalism, Mirror Editor Piers Morgan complained woman freelancers ‘just don’t push themselves forward’. Though often bombarded by proposals from men, he got ‘maybe four letters a month from women suggesting stories.’[25]

The only exception we found was for writing competitions, where for some reason women seemed less inhibited: perhaps because competitions seem more of a lottery, and so less personally threatening; perhaps because it’s easier for them to find the time to complete a single poem or short story for a competition.

A fair reading

Even if a woman does muster the confidence and carve out the time to start – and edit, and polish – a complete manuscript, research shows her work is unlikely to be judged on its merits. Just like in school. In a now-famous experiment by Philip Goldberg in the 1970s, manuscripts by John T McKay were consistently judged as cleverer, better, superior in every way to identical manuscripts by Joan T McKay [26]. As Norman Mailer once candidly remarked: ‘A good novelist can do without everything but the remnant of his balls’.

This finding has been replicated over and over again during the intervening years: with male and female teachers, male and female students, with boys and girls; with academic treatises, short stories and poems. Just last year psychologist Amy Surmann found that writing attributed to a woman author was judged less clear and less competent than when attributed to a man [27].

'manuscripts by John T McKay were consistently judged as cleverer, better, superior in every way to identical manuscripts by Joan T McKay'

‘That’s why you don’t need to read women’s writing to know it’s no good,’ says Dale Spender. ‘The only reason I ever got published is because they thought “Dale” was a man. Imagine if I’d been called Dolly! I’d never have been taken seriously.’

Charlotte Brontë understood this when she submitted Jane Eyre under the pseudonym Currer Bell. At publication there was some debate over the gender of Currer Bell and it was generally acknowledged that ‘if the novel had been written by a man it was a marvellous achievement, but if written by a woman it was scandalous’ [28]. When the apparently male author of Adam Bede was revealed to be a women: ‘It is quite clear that people would have sniffed at it had they known the writer to be a woman, but they can’t now unsay their admiration.’ [29]

Even when the subject matter is ‘feminine’ it is accorded more respect when handled by a male author. A Ted Hughes poem about the natural world, or about love, is seen as having a gravitas, a muscularity, not accorded, say, to the poetry of Selima Hill. And Anthony Trollope’s painstakingly-observed gossip novels are seen as politically astute, whereas his descendant Joanna’s painstakingly observed gossip novels are disparaged as mere ‘Aga-sagas’.

But for women to tackle more ‘masculine’ subject matter is not necessarily the answer. ‘A man who reviewed my Procedures for Underground … talked about the “domestic” imagery of the poems,’ complained poet and novelist Margaret Atwood in Sexual Bias in Reviewing, ‘entirely ignoring the fact that seven-eighths of the poems take place out of doors’. [30]

‘If an all-woman shortlist had been announced, there would have been all kinds of accusations of bias’

Woman authors, it seems, just can’t win. Indeed, it was the complete absence of women on the 1991 Booker shortlist that prompted Kate Mosse to start raising sponsorship for a woman’s fiction prize. ‘If an all-woman shortlist had been announced, there would have been all kinds of accusations of bias,’ she told us. ‘But an all-man shortlist hardly raised an eyebrow.’

Four years on from the first Orange Prize in 1995, she believes it has had an enormous effect. ‘It’s encouraged debate about literary prizes, about the subjectivity of judges. And it’s helped debunk the idea that there are “good books” and “bad books”.’

Cures for mslexia

If women have the innate ability, then they have the potential to be just as good – if not better – than male writers. And to be recognised as such. All they need is what male writers already have: time, confidence – and a fair reading.

Mslexia magazine will tackle these issues systematically in the coming years. We will be looking at women’s lack of time and asking whether arbitrary age limits – for grants and prizes, for example – effectively discriminate against women whose writing lives tend to be so much more fragmented than men’s. Or whether special bursaries could be earmarked to help writing mothers with the costs of childcare.

Topics like this – housework, solitude, rotas – will all be looked at in the magazine. Writing time is so important: seizing it, stealing it, managing it, will be recurrent themes. If that means a time-and-motion analysis of manual washing-up versus dishwashers, you’ll find it here in the pages of Mslexia.

If confidence is your problem, we’ll be reporting on the latest psychological research into creativity and suggesting ways you can boost your output, your originality – and your ability to cope with rejection. We’ll be discussing courses and writing groups and how they can work for you. There’ll be features on reading aloud, on performing for an audience – and on stage fright.

'we’ll be reporting on the latest psychological research into creativity and suggesting ways you can boost your output, your originality – and your ability to cope with rejection'

And we’ll be doing what we can to ensure your work gets a fair reading. That’s why we’ll be examining the publishing world itself, talking to the people who work in and around it. We’ll be telling you what agents and editors are looking for – and, just as crucially, what puts them off. That’s why you’re as likely to find a feature on envelopes or type size in the pages of Mslexia as you are to read an interview with an editor at Fourth Estate.

Another question we’ll be tackling regularly is how women’s writing is assessed. In the next issue, for instance, we’ll be looking at this year’s Orange Prize shortlist and asking whether women write differently to men.

Things have changes a great deal since Charlotte Brontë’s day. Women now outnumber and outperform men at university. We can decide when and whether to have children. We can decide to make writing our priority – if we want to.

The latest UK census revealed a dramatic increase in the numbers of women who have done just that. From being just 34 per cent of people whose main occupation was writing in 1981, ten years later the number of women had increased to 43 per cent [31]. And that’s not including the many thousands writing part-time, in snatched and stolen time, in ‘that still blue almost eternal hour before the baby’s cry’.

There’s no time to waste whinging. Stick with Mslexia and we’ll help you all we can.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Debbie Taylor is the founder and Editor of Mslexia. She revisited this topic with updated statistics in 2017.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

SOURCES

1. Halpern, D F, Sex Differences in Cognitive Abilities, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1986

2. Office for Standards in Education, 1998

3. Universities Statistical Record, 1995, Vol. 2

4. The Reading Partnership Survey, 1997

5. Books and the Consumer: Report for Non-subscribing Companies Based on 1997 Data, Book Marketing Limited, 1998

6. Social Trends, Office of National Statistics, 1998

7. Women in Management in Publishing survey, reported in The Bookseller, 1992

8. Mslexia survey, 1998

9. Chappel, J A and Polland, A, The Letters of Mrs Gaskell, Manchester University Press, 1966

10. quoted in Olsen, T, Silences, Virago, 1980

11. Sieghart, M A and Henry, G, The Cheaper Sex: How Women Lose Out in Journalism, Women in Journalism, 1997

12. Tweedie, J, In the Name of Love, Jonathan Cape, 1979

13. quoted in Olsen, T, op cit

14. ibid

15. ibid

16. Spender, D, Man Made Language, Pandora/Rivers Oram, 1997

17. Spender, D, Mothers of the Novel: 100 Good Woman Writers before Jane Austen, Pandora, 1983

18. Rich, A, On Lies, Secrets and Silence: Selected Prose 1966-78, Virago, 1980

19. Pajares, F, and Johnson, M,J, ‘Self-efficacy beliefs and the writing performance of entering high-school students’, Psychology in the Schools, Vol. 33, 1996

20. Spender, D, and Sarah, E, Leaming to Lose: Sexism and Education, Women’s Press, 1980

21. ibid

22. reported in Spender, D, Invisible Women: The Schooling Scandal, Women’s Press, 1989

23. Baer, J, &lsqu