One of the first writing courses I ever taught was in 1987 at the City Lit in London. I read my students’ work in advance and went round each of them in class afterwards offering one line of praise – ‘Your character is really vivid to me, and so memorable’ or ‘There is a real sense of place here’ – followed by one suggestion for where I thought work was needed – ‘Maybe the structure needs looking at’ or ‘I don’t feel I know this character’.

I didn’t tell them that this was what I was doing. And I carefully prepared what I said so that my comments would be both truthful and specific to the piece of writing I’d read. I gave them a while for my comments to sink in then went round the group and asked them to repeat my comments back to me.

You know what I’m going to say, don’t you?

Yes – every one of them repeated back the critical remark, sometimes making it much more negative than what I’d actually said. My comment on structure needing attention, for example, became ‘You said I can’t do plotting at all!’ It was clear to me then that a criticism goes straight to the heart of a writer. Goes in deep and lodges there.

Not one of the students remembered the positive thing I’d said. When I mentioned the praise, or repeated it word for word, some seemed astonished – some even denied I’d said it at all.

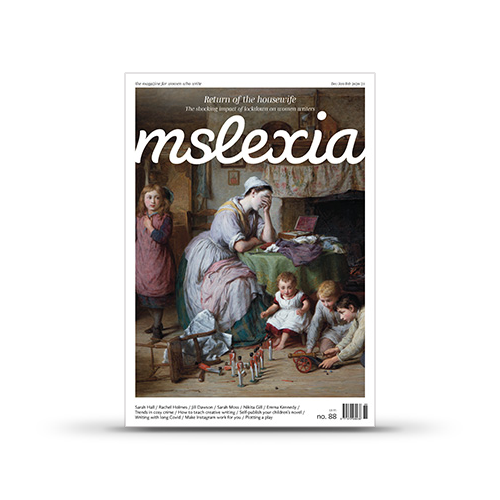

Was it just forgetfulness? Or an inability to hear the praise in the first place? Or perhaps they’d felt hesitant about repeating aloud my positive comment in front of the whole group. Maybe my group were unusually modest; or maybe the critical comment felt more useful to them. But given that this workshop was largely made up of women (as is every other creative writing group I’ve ever taught), I wondered how uncomfortable women in particular feel about receiving praise and sharing it with others.

If so, does it matter?

Well yes, it does matter – because I’m convinced that praise really helps a writer develop. If that’s true, then being unable to hear and/or remember praise is a serious issue for women writers.

When I taught on the most famous MA in Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia I didn’t use praise as freely as I do now; it wasn’t part of the accepted teaching model. But these days I believe it’s the best tool that I have as a tutor; used generously and constructively, it gets pretty astonishing results.

Like every other writing tutor, I am often asked ‘Can you even teach creative writing?’ But we are rarely asked about the methods we use to teach our subject. In fact the so-called ‘peer review model’ is the only model most writing students are offered. This takes the form of a workshop led by a professional writer with all participants – students and tutor – encouraged to offer advice and criticism on the work in progress.

Those attending such workshops sometimes forget that very few writers who teach creative writing – whether it be a university undergraduate or postgraduate course, a residential week at an Arvon centre, an evening class or Faber Academy course – have had any kind of teacher training. It is assumed (insultingly, in my view) that because someone can write, they can teach.

In those early days of teaching at the City Lit I was a newly qualified yoga teacher. And in the absence of any guidance on how to teach writing, I used what I’d learned during my training to be a yoga teacher – and simply applied it to my creative writing classes.

This was as follows: show how to perform a yoga asana by demonstrating it yourself. Then encourage people to have a go and adjust them until they are in the right position, using reassurance – ‘Yes, your arm should rest there’ – telling them exactly what they are doing right. With yoga the emphasis is on each individual reaching their own potential according to their age, fitness and flexibility, as opposed to an idea of a one-size-fits-all perfect posture,

My interest in how we learn was further developed by having a child on the autistic spectrum, who often seemed unteachable. He simply could not learn by negatives. If you told him not to do something he would do it. If a teacher asked him to ‘Stop standing on that chair!’ he only seemed to hear the ‘standing on that chair’ part. At the time Educational Psychologists assessed him as having something called Oppositional Defiance Disorder, now known as Pathological Demand Avoidance or PDA. But to me it seemed less like a disorder and more like a common personality trait – one I share, if I’m honest!

Because how many of us do respond well to negativity and criticism? Don’t most of us just shrink inside and put that work to one side, unsure how on earth to fix it? We do respond to positivity, however. My son certainly did and loved being told what he was doing right. Careful rephrasing made a huge difference, as did written rather than verbal instructions. ‘Stand on the floor now,’ would work where ‘Stop standing on the chair’ wouldn’t. He was clever if encouraged; sulky and stubborn the moment you suggested he had done something ‘wrong’. If you identified what he’d done right, he could build on that, and do more of it.

My writing students are more sophisticated intellectually, but their emotions are the same. Writers find it painful to be told what they are doing wrong. Having a son with PDA taught me the value of careful phrasing, of not using sweeping criticism, and of offering clear instructions for improvement. I regret the time I spent teaching before I understood this.

These days I use the techniques from yoga teaching, and from my experience of psychotherapy, neuroscience and autism: of listening, reflecting back, carefully reading the students’ work. Then I point out how the writing is succeeding: ‘This bit’s terrifically funny’; ‘I can really hear that character’s voice here’; ‘The suspense there is great’. I am well aware that this is subjective, but I am a reader as well as a teacher, which means my comments are always truthful and often have an almost miraculous effect, bringing a real lift in energy and focus for my writing students. It astonishes me how rarely writing tutors do this or think it worthwhile.

By offering praise I’m not soft-soaping my mentees. And I do, of course, offer suggestions any issue that need work. But it’s done in a positive context. They know that I am enjoying the work and that I believe it can be good.

This is a recognised pedagogical technique known as the Pygmalion Effect, identified by psychologists Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobsen back in 1968. They were looking at the effect of teacher expectations on the performance of their students and discovered that a teacher’s favourable expectations had a positive influence on student performance while unfavourable expectations had a negative influence. And they locate the responsibility with the teacher. ‘When we expect certain behaviours of others,’ they concluded, ‘we are likely to act in ways that make the expected behaviour more likely to occur’.

In their classic experiment a teacher is led to believe that three particular children are especially good at maths. (In fact the children had tested average.) At the end of the year these three children’s maths abilities were found to be in the exceptional range. The teacher had not necessarily praised the children, but through body language had managed to convey to the children that their abilities were exceptional – and the children transformed the teacher’s belief into reality.

The Pygmalion Effect has also been shown to work powerfully in the business world – Shawn Achor’s book The Happiness Advantage cites a huge amount of research. He also mentions an experiment carried out with a group of Asian women at Yale University in the US. Prior to a maths text, the group were casually told that ‘of course women tend to be worse than men at maths’. The following week they were given another maths test. This time they were told: ‘Of course Asian people tend to do well in maths and many maths geniuses are Asian’. You guessed it: on this occasion they had improved scores. This time it was the students’ self-belief that was in operation here, primed by the teacher’s casual remark.

Why should the world of creative writing be any different? Indeed, I can think of many examples of a writer flourishing once an author they admire shows belief in them – Andrew Miller cites Angela Carter; Louise Doughty, Malcolm Bradbury; and I’m indebted to Jane Rogers and Caryl Phillips.

Toni Morrison once said that teaching creative writing was teaching her students to read their own work properly. We develop as writers once we understand how to do this: bringing those barely formed ideas to the surface, challenge ourselves, learning what we can do. Students – writers – grow into the shape you hold for them, just as I demonstrate the shape of a yoga asana.

When praise is genuine, based on actual examples, it has an amazing impact on a writer. If I ever needed evidence that it works, I only have to look at the growing number of books on the shelves in my study, sent to me by my newly published students, with their lovely inscriptions of heartfelt thanks.

JILL DAWSON is is an award-winning poet, anthologist and author of ten novels; her most recent is The Language of Birds, about the nanny murdered by Lord Lucan. She runs Gold Dust Mentoring Ltd, a scheme which pairs new writers with established ones.