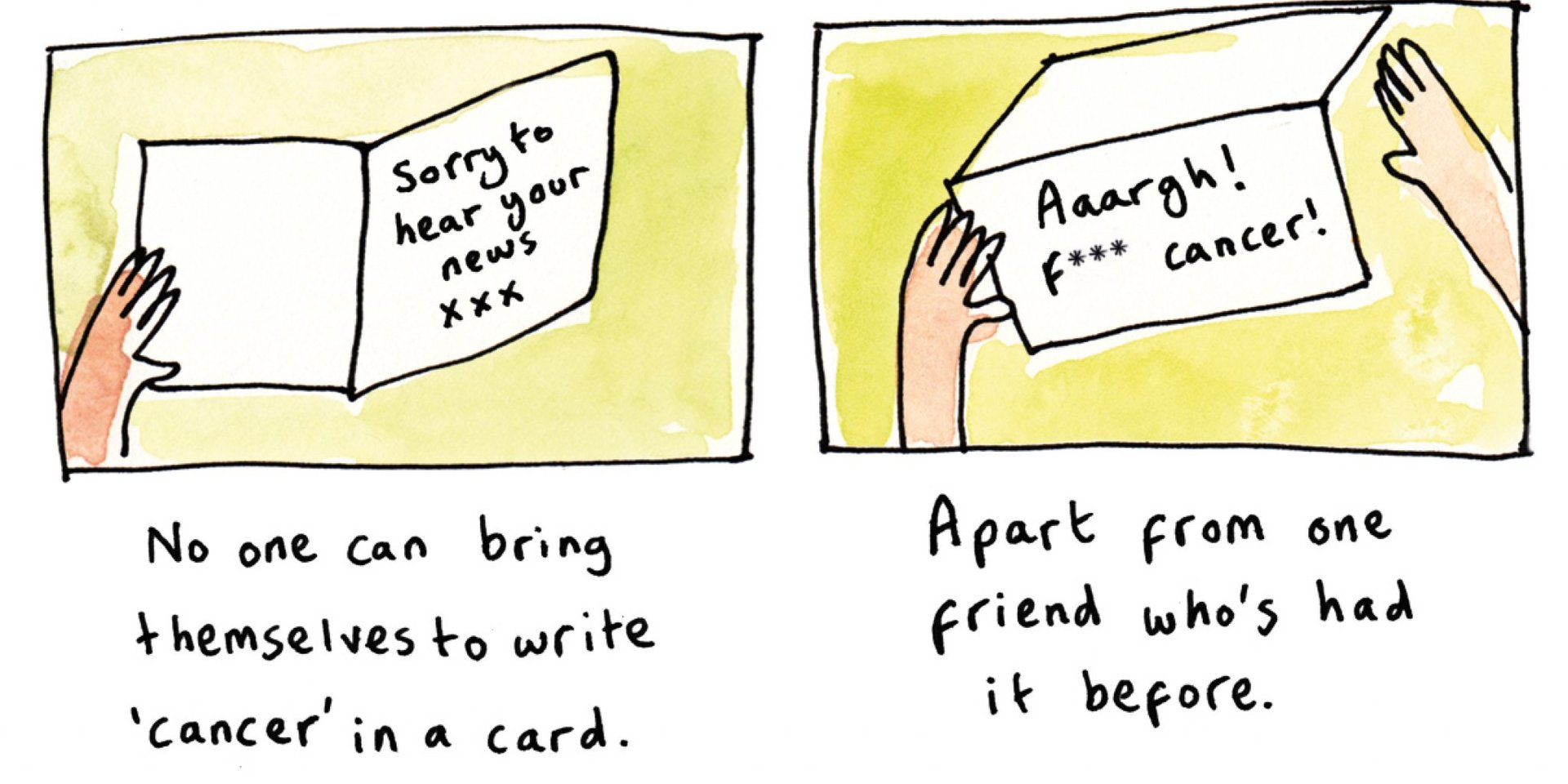

I started writing diary comics and posting them online to inform people about my experience of illness and disability, caused by a bowel cancer diagnosis during my first pregnancy (my son is fine now and so am I).

Sharing my comics really helped me to feel less alone in that experience. Other cancer patients and supportive readers got in touch to cheer me on, and I was able to let people know how I was feeling, how treatment was progressing, and what they could do to help, without having to have the same upsetting conversations over and over again.

I could also educate people about what symptoms to look out for, and give healthcare workers a better understanding of what it was like to be a patient, by drawing those exchanges that made me feel well cared-for – and those (few) that left me feeling baffled, dehumanised or not taken seriously.

It gave me something to do during long stints in hospital. Fascinating and funny characters came and went the whole time: kind and charismatic doctors and nurses; chatty porters; very old patients talking about their amazing lives – fudge, fags and running for the bus are the secret to longevity, apparently. There was suspense, grief, fear – all the things that make for a great ‘story’, although it was actually my life!

But comics about ‘small’ things can be just as moving, poignant and meaningful as comics about life-changing events. Everyday moments can grab a reader who recognises the situations that you describe.

And it’s therapeutic. When I’m concentrating on how to draw something, I stop thinking about how I’m feeling. I start enjoying making artistic and narrative choices. It feels emotionally beneficial to put my thoughts in order and ‘get them out’ on paper, to acknowledge the things I’m worried about.

But therapeutic value and artistic value are not mutually exclusive. Diary comics are also an incredibly rich, varied, experimental, complex political art form that can say so much about people and society. They can give a voice to writers who are marginalised for any reason. And they cost very little – you don’t need expensive equipment or a studio, just a pen and paper.

Why write comics rather than a ‘normal’ book? There are so many reasons! A picture communicates meaning in an instant, and can transmit thoughts and feelings that are hard to describe with words. You can tell stories in any direction, leading the reader’s gaze across the page in any way you like – left, right, up, down. You can break up the page however you choose, or not break it up at all and tell a whole story in one image.

Adding text adds another dimension. If you draw something happy, then write something sad next to it, the essence of the whole thing is heightened. It’s like magic when this happens. If you draw something mundane then write something weighty next to it, suddenly those small everyday things hold a greater significance.

You don’t need to be brilliant at writing or drawing to write fantastic impactful comics. You just need a pen or pencil and something to write about. A drawing doesn’t need to look realistic or be full of detail to communicate meaning – rough, scrappy and pared-back drawings can do this too. The more you draw, the more comfortable you will become with the process, and a style will develop that feels uniquely yours.

Working out your own visual language is brilliant fun. Different line qualities and choices of material can say something about how you’re feeling when you make a drawing: confident and bold, upset and wobbly, excited and all-over-the-place.

If you’re drawing a person, think about the shapes or marks that would best describe them. What do they really look like? Do they have a long head or a round one? Close-together eyes or far apart? How simple can you make the drawing? I give myself the same scribble of hair in every drawing. My hair doesn’t actually look like that but it means you can always identify which character is me. (If you don’t feel like drawing people, you can use abstract shapes to represent characters instead. A felt-tip blob or cut-out shape could speak, just like a person might.)

Your text can be as expressive, visually, as your drawings. Think about how it fits around your drawings and becomes part of the image. Will you put your text underneath the drawing, or scattered around it? If I’m shouting, my writing is larger and often in capitals. If you’re using speech bubbles, you can have fun with the shape of the bubbles too: make them spiky or jagged for angry speech, smooth or soft-edged for ordinary conversation. Think of every strip as an experiment and see how it goes.

Once you get in the habit of writing a diary, you will notice more, and things will strike you as significant in a way that they didn’t before. By working out how to describe a scene you will remember moments and conversations in greater detail too, and images with more clarity.

When you write diary comics you invent a version of yourself. The character you see in my comics is a version of me – but she isn’t really me. She starts conversations that I want to have; she swears more than I do; she says the funny things that I only think of in real life when the moment has passed. (I draw myself but you don’t have to. You could draw what you see, rather than putting yourself in the strip.)

A diary isn’t just a list of things that have happened. It’s a constructed world. You decide what to include or leave out. You have control over the stories you want to tell. It’s interesting to see which of my comics appeal to people. I’ve found that strips that share personal moments seem to strike a chord. It’s tempting to respond to this by sharing more and going deeper, but I don’t think that’s healthy. I try to write for myself, and that works fine.

Writing a diary comic is also a great way in to writing something larger. When I wrote my book about cancer and pregnancy – Probably Nothing: A Diary of Not-Your-Average Nine Months – I didn’t set out with the intention of writing a book. I started writing simply because there was so much to say about how my life had changed. I didn’t know what was going to happen, whether I’d survive, whether my son would survive. I kept writing until the end of my treatment when he was six months old – a good end point to that story.

A similar thing happened with my latest book, My Day in Small Drawings, which is a collection of diary comics that I wrote during lockdown, which I turned into a guide to comic drawing.

When the first lockdown started we were at home with our son, trying to find ways to keep him happy. The things we found to do together were funny and memorable – karate with a 1kg bag of raisins, giving each other makeovers, screaming at tin-foil – and it felt important to write down and remember those things.

I also wanted to record how the social and political situation affected us. Like everyone, I felt anxious and stuck. Making comics helped me get through it. Then at the end of lockdown I had a box full of sketchbooks and thought – Ah! This could be another book!

The comic form, in the way that I do it, (quick, scrappy, visual notes rather than polished drawings) keeps things low-pressure. My strips are short, self-contained creative experiments. Building a collection of comics in this way, gives you material to work with if you do want to write something longer. You will start to see patterns and themes, ideas that you return to, storylines that have developed, the progression of a narrative. Then you can build on them, explore further the strips that you really enjoyed writing, save characters or scenarios to use in other stories.

My Day in Small Drawings is about getting past the idea of writing something epic and just starting to write, using diary comics as a way in. I hope my love for diary comics has rubbed off on you, and that you might try it too!

INSPIRATION

· Graphic Medicine is a resource for comics about illness and healthcare, authored by patients, healthcare workers, carers and people who have experienced illness: graphicmedicine.org

· Positive Negatives is a not-for-profit group based at SOAS university in London producing comics about international human rights and social issues, conflict, migration and asylum. Artists and writers collaborate with people who want to share their testimonies: positivenegatives.org/resource/articles/

· Art School for the Homeless has created ‘the world’s first ever graphic novel by people affected by homelessness’: accumulate.org.uk

· LDComics is the largest women-led comics forum in the UK, open to all: ldcomics.com/about-us/

Below are some of my favourite diary comic artists and memoirists.

- Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel

- The Times I Knew I Was Gay by Eleanor Crewes

- Cancer Made Me A Shallower Person by Miriam Engelberg

- Good Talk: A Memoir in Conversations by Mira Jacob

- Heimat: A German Family Album by Nora Krug

- A Puff of Smoke by Sarah Lippett

- Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi

- Maus by Art Spiegelman

- The March Trilogy by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin and Nate Powell

- Billy, Me and You by Nicola Streeten

EQUIPMENT

· Fineliners are my go-to choice for pens (the Pigma Micros 05 is my favourite at the moment). The lines are clear and the marks consistent and easy to control. For a bit more variation try a soft pencil or ink and a dip pen.

· If you want to add colour use good-quality colouring pencils like Fabel-Castell or Caran d’Ache.

· I prefer drawing on paper to drawing digitally. I like the fact that I can’t correct everything! I use plain A5 newsprint notebooks from Muji. The paper is smooth and they are small and light enough to carry around

MATILDA TRISTRAM is a writer, illustrator, animation director and producer with over ten years’ experience working in children’s media. She has written for multi-award-winning TV shows, such as Peppa Pig, Sarah and Duck, Dipdap and Morph. Clients include Blue Zoo, Aardman Animation, Ragdoll Productions and The Elf Factory. She posts regular comics on Instagram @MatildaTr