It's trite but true that when you hit a certain age you find yourself musing on your childhood. It's a tricky activity for a writer. Musing tends to lead to writing, and if you're going to be honest about your early life, other people's feelings may be hurt.

If you leave it for long enough, of course, those most likely to be upset will be dead and you can plunder their lives at will. Nina Bawden is my role model here. I once heard her say, 'Writers are terrible people. Even as you sit by the deathbed of your beloved, you say to yourself, "All this is grist to my mill"'.

I've had an exciting life as an adult. I’ve been bitten by a snake in the South China Sea, charged with murder in Ethiopia, and forced to flee from a gun battle in Beirut.

My years living in Malaysia, Ethiopia and the Middle East produced a crop of YA and children's novels. Exploring Iraqi Kurdistan in the 1970s led to Kiss the Dust. Nine rather too exciting months in Lebanon during the civil war produced Oranges in No Man's Land. Working in Syrian refugee camps in Jordan resulted in Welcome to Nowhere and A House Without Walls. And getting to know a gang of street boys in Addis Ababa was the spur for The Garbage King.

Other books came out of time spent in Gaza and Ramallah, a visit to Pakistan to research the trafficking of young camel jockeys, and many trips to East Africa, working with the Kenya Wildlife Service to create my Wild Things series of ten novels about animal conservation.

Then came Covid and lockdown. But instead of feeling trapped, I felt weirdly liberated. I was exhausted by the intensity of hunting for great stories in difficult parts of the world, using every sense to soak up sights, sounds and smells, meet and listen to as many people as I could, and scribble, scribble, scribble at the end of every exhausting day in battered notebooks and diaries.

Suddenly, that was over. And in the deep peace that lockdown brought, I let my mind roam.

My early life bubbled up into my consciousness. At night I lay awake revisiting the creaky old house I'd lived in as a child. I heard my brother clattering down the stairs, listened to my older sister revising for exams, smelled the acrid smoke from the coal fires that warmed the house, and watched Mother taking trays of oatcakes out of the oven.

Then that strange alchemy, that every novelist knows, began to work. And the shapes of my parents, my brother and sisters, our house and our garden, my school and all that went with it, began to melt and merge, taking on new forms as they slowly turned into fiction.

Whole rooms disappeared from the house and new ones were added. One sister acquired a beautiful singing voice. The other married a doctor. Our brother became a handsome rebel. Our mother was sharpened, our father was softened. After a period of change and gestation, they emerged like butterflies from their chrysalises, whole new characters that I could move around as I wished.

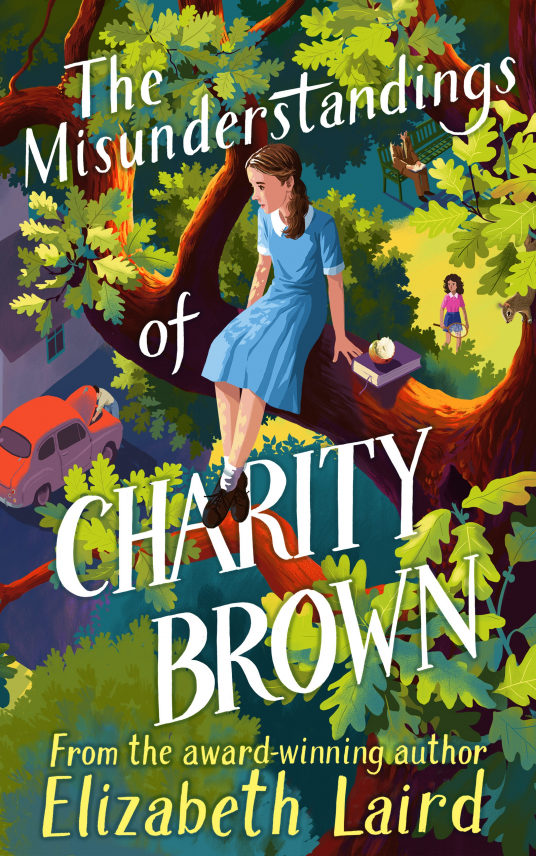

The result of all this remembering and transformation is The Misunderstandings of Charity Brown, my latest novel.

Were you to ask me the following questions, here's what I'd answer:

Is Charity Brown you as a child? Yes and no.

Are the other characters in the book based on real people? It depends what you mean by real.

Did the events you describe actually happen? I honestly no longer know what was real and what I've imagined.

What I do know is that my fictional Charity Brown's fictional family belongs to a small, fundamentalist evangelical protestant sect. So did mine. Her Scottish parents kept Sundays apart from every other day. We did too. Our house was open to visitors from all over the world: some working with my father's Bible-reading organisation, others needing time to rest and recuperate. Some people stayed with us for months.

Charity has just turned 13 and must now find her place in this restrictive world. She doesn't become an all-out rebel, but she questions, doubts, pushes at boundaries, and comes to her own conclusions. And that's what I did too.

And this is where I hope the novel might have meaning for any young teenager living in a tight religious family, whatever faith they belong to. They have the same dilemma I had. How far will they allow themselves to question their parents' world, with all the risks that entails?

As I let myself melt into my 1950s childhood over the weeks of lockdown, I was startled by how intensely real it was to me – and by how much the world had changed in the intervening decades. My mind slipped easily back across those 65 years, until the 1950s seemed normal again and it was the modern world that seemed strange.

'I was born during the War,' I told my young editor at Macmillan.

'Which war?' she asked.

She was deeply shocked by the sexism and racism in the book, that was so prevalent in Britain then. She’d never heard of the panic that swept the world during the polio epidemic. She marvelled at the weirdness of pre-decimal currency and the filthiness of smoggy London.

When a novel is written and you finally lay down your pen, it takes a while for it to leave you. The characters slowly turn and walk away, the settings gradually fade. But this novel is different for me. Charity Brown isn't going to leave me for a long, long time.

ELIZABETH LAIRD was born in New Zealand to Scottish parents. The family moved to Britain at the end of WW2 when she was two. She is the multi-award-winning author of over 20 novels for middle-grade readers, including The Garbage King, The Prince Who Walked with Lions and A House Without Walls, as well as four picture books for young children and five collections of folk tales. She has been shortlisted for the prestigious CILIP Carnegie Medal six times and Welcome to Nowhere, her novel based on time spent in refugee camps in Jordan, was the winner of the UKLA Award, a book award judged by teachers. Elizabeth’s new novel, The Misunderstandings Of Charity Brown (Macmillan), was released on 7 July.

ELIZABETH LAIRD was born in New Zealand to Scottish parents. The family moved to Britain at the end of WW2 when she was two. She is the multi-award-winning author of over 20 novels for middle-grade readers, including The Garbage King, The Prince Who Walked with Lions and A House Without Walls, as well as four picture books for young children and five collections of folk tales. She has been shortlisted for the prestigious CILIP Carnegie Medal six times and Welcome to Nowhere, her novel based on time spent in refugee camps in Jordan, was the winner of the UKLA Award, a book award judged by teachers. Elizabeth’s new novel, The Misunderstandings Of Charity Brown (Macmillan), was released on 7 July.

Twitter @EMRLaird